All the teachers described here are given pseudonyms to protect their real identity.

Sister Mac

Sister Mac taught piano at my primary school. I had several years of lessons with her as did some of my friends. I don’t think any of us were ever going to become fantastic players or go on to study at the conservatorium, but it was probably seen as part of a rounded education, being able to play an instrument.

Music lessons should be a thing of joy. All those optimistic parents that want their children to learn to play the piano, perhaps imagining them becoming world-renowned, like Liberace or Lang Lang.

The music room was on the ground floor of the convent building where the nuns lived. I remember it as a small, disorderly room. There was a piano against the wall opposite the door, and a table with some chairs where we sat for theory lessons, which must have taken place on weekends. There must have been some other furniture in the room as I remember clutter – stacks of paper, books, music sheets.

Sister Mac was old. It’s hard to know how old she really was because I was so young, and everyone over the age of 20 was old, but I’m pretty sure she was past retirement age. She was very old. She was small, bird-like, hunched over, and I remember her face was very heavily lined.

Music lessons should be a thing of joy. You’re learning how to make music, to create sound, to master an instrument. Some times music lessons were joyful. You got the notes right, Sister Mac was in a good mood, you came of the music room feeling happy.

But lessons didn’t always go this way.

Some days you hit the wrong notes, or you struggled with a particularly difficult piece or section, or maybe you hadn’t practised that week, or maybe this was a new piece you were still getting to grips with.

Some teachers would exhibit a degree of patience in this case, take things slowly, give you time to understand the music, the notation. Sister Mac was not one of those teachers. She was prone to outbursts of unbridled anger.

Got the notes wrong? She would grab your hands and grind them into the keyboard against the correct notes. “This is how it goes,” she would shout.

(And yes, of course it hurt.)

Sometimes she would take a ruler and smack the back of your hand for getting the notes wrong.

(And yes, the fear of getting another crack of the ruler did nothing for accuracy.)

Sometimes she would slap you in the face, and then hug you when you started crying.

(And yes, very few of my friends continued on with music.)

She may have been slightly demented, but she obviously knew what she was doing was wrong because after particularly tearful lessons, students were made to go out into the playground and run around to have the wind dry the tears on their faces.

When you finished your lesson, you then had to go and fetch the next person for their lesson. Never have I felt more like the harbinger of doom than knocking on the door of a classroom and seeing all the music students look panicked, wondering whose number was up. “Could Joan Smith please go for her music lesson with Sister Mac?” Several relieved faces, only Joan looked terrified. There would be a whispered conversation in the hallway. “How is she today?” “She was okay with me, but she’s in a bad mood so be careful.” The music students shared information so you knew how to prepare yourself.

My mother used to work as a volunteer in the school tuckshop, and she remembers seeing a friend of mine coming in to get her lunch, hiccupping with sobs, her face red. “What’s wrong?”, my mother asked, concerned to see a child in such distress. “I’ve just come from my music lesson,” my friend said.

People knew Sister Mac used to hit the kids. Everyone knew their kids hated music lessons because she was so mean and cruel, and because she was mean and cruel they hated music and didn’t want to practice, and the more they didn’t practice, the worse they became and the more likely they were to get hit. I don’t think any parents ever spoke up about it, or if they did, the attitude of the school probably would have been, If you don’t like how Sister Mac runs these music lessons you can always go somewhere else. This was the 70s after all, corporal punishment was still common in schools (certainly in mine) and challenging the might of the Catholic Church was probably not something most parents would’ve done.

Music lessons should have been a thing of joy.

The Pink Lady

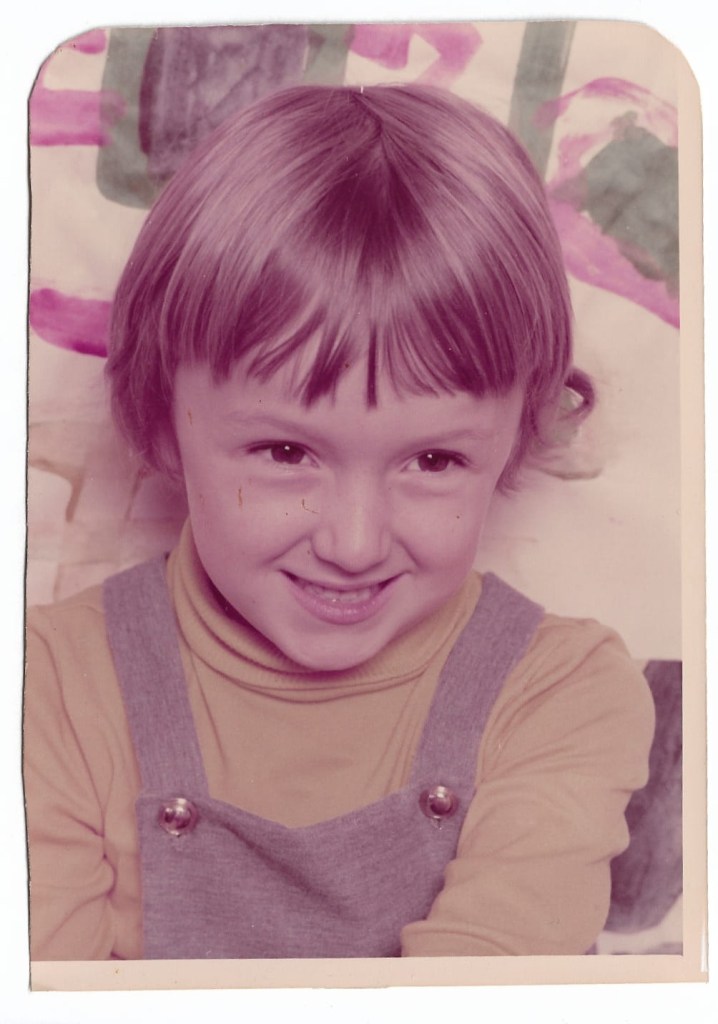

It was my first year at school, so I was very young and also super keen. My mum had been telling me for years that going to school is a big adventure; it meant I was a big girl now, and there would be people there who could answer all my questions.

(My mother had already realised three children before me – children who were probably slightly better behaved and lower maintenance than me. By the time I came along, I think she was tired and a bit bored with answering the same questions that she’d already answered several times before so she made school sound really exciting so I was really looking forward to being there.)

I remember being confused about school. I didn’t understand that I shouldn’t go and help other people with their work. I knew my letters. I could read a bit. Some of my classmates were struggling with this, so as there was only one teacher in the class I thought it would be good to help.

Apparently this isn’t what you do, and it isn’t good.

I got into trouble with my teacher because I was always out of my chair, always talking to other students. She saw me as a distraction, a chatterbox, someone who didn’t understand the rules.

Eventually, after a conversation with my mother, she came to the realisation that I was slightly ahead of the other kids, so we came up with some strategies to help me be less distracting. If I finished my work, I shouldn’t try and help other students. Instead, I can go sit in the library corner and read a book quietly. This worked well for me (even though a lot of the books were of the A is for apple variety, not a lot with actual stories).

The teacher for the other first grade class was the one I didn’t get along with. Maybe she was covering our class one day and in my chatty / no filter younger days I said something to upset her. I can’t remember. But something happened at school one day and she pulled me up in front of class. She had her face in my face, shouting at me and poking me in the chest with her long fingernails. That hurt.

My overriding memory of this event is that whatever the issue was, it wasn’t my fault. The details have faded but the sense of injustice remains, along with the memory of those fingernails jabbing at me.

I don’t know if it was this instance or another, but she kept me in after school one day. I was five years old. My friends had all left the classroom and I was there alone, to redo work or to sit in my righteous indignation until I was prepared to apologise (for something I hadn’t done! Oh, that would have burned my righteous little heart!)

As time ticked away and I worried about my mother worrying about me getting home late, I did what I had to do to get out of that room.

I packed up my little bag as fast as I could, shoving stuff in and running out of the room, away from that horrible woman. I remember I was crying.

And I remember as I was running I tripped over my shoelace and I fell roly-poly down a slope of rough gravel near the school gates. I got up, crying even harder due to the grazes on my palms and knees.

I remember looking up and seeing a friend’s mother driving past. She saw me standing and crying, stopped her car and mouthed at me, “Are you OK?” I just shook my head, picked up my bag, and set off running for home.

I think after this event my mother did approach the school – rightly so, after I arrived home late, crying, hands and knees full of dirt and gravel – over something that wasn’t my fault. (As I’m writing this, the memory is coming back. I’m sure the Pink Lady blamed me for something that I hadn’t done.)

I don’t want to give the impression that I was an angel child that never did anything wrong, because I’m sure at some point I did. (Playing in the storm drain for instance – I got a rollicking for that from my parents because I did what I’d been told not to, and because it was dangerous and of course in our local community, someone who knew my parents had seen my friends and I in the drain and reported it back. This was social media before there was social media.)

However I have several remembered interactions with the primary school hierarchy that seem to centre around them deciding to assign blame first and ask no questions.

Sister Brandon

Sister Brandon was of the old fashioned mentality that little girls should be neat and quiet. Neatness and quietness were next to godliness for Sister Brandon. Here is where we hit a difficulty, with me not being neat in my appearance or in my handwriting. I was also probably seen as difficult due to my habit of asking questions. Teachers like Sister Brandon didn’t like questions. Questions were tantamount to doubting what she told us.

Every week, Sister Brandon assigned us a writing task for the weekend. I loved writing (nothing has changed there) and liked to spend my Friday nights writing my essays. I can’t pretend they were quality essays (I was 11) but I wrote furiously as ideas came to me.

Furious writing is not tidy writing.

Untidy writing does not get good marks from Sister Brandon.

What does get good marks is insipid stories in perfect cursive. I’m pretty sure one of my classmates got an A for a one page story that went along these lines:

On Saturday it was sunny. We went out in our boat. We went on the river. We had a good time. Then we went home.

(Do I even need to mention that this particular girl always had neatly done hair, never lost her hair bands and would never had asked difficult questions in class?)

My multi-character, involved stories were regularly returned with a D and a comment “poor handwriting.” Nothing about plot or structure or characterisation.

I remember consulting with my mother on how to deal with this. She suggested writing what the sister wanted. So one week I wrote an equally stupid story to the one above but in my best handwriting. Sister Brandon was pleased. “See, it’s not so difficult.”

Ah but it is, Sister Brandon! It’s very hard indeed, because you’ve taught me that I have to make myself less, so much less, to be acceptable, to be seen as a good girl. That the little girl I was, the one who liked to ask questions, who always wrote long essays, and who was forever losing her hair bands; you’re telling her she was too much, and she should make herself be less to be acceptable.

Sister Stella

It was a rainy day so I had come to school with an umbrella. It wasn’t a great umbrella. It had been in the family for some years, and was maybe a bit faded, but it still kept the rain off. When I got to school my umbrella was left on the bag rack outside my classroom with my school bag. The rain stopped during the morning, and at lunchtime it was a surprise to see one of the boys in my class in the playground with my umbrella.

“Hey! That’s my umbrella! Give it back!”

(Retrospectively I realise in the repressed way that boys express their feelings, this particular boy might have liked me, and this was a sure way to get my attention.)

He ran off, waving the umbrella above his head, making me chase after him. He pretended he was going to break the umbrella and that made me more anxious and angry. If he broke that umbrella not only would I maybe get wet on my walk home, I would be in trouble with my parents. That broken umbrella would somehow be my fault. I know I could be careless with belongings – I might lose an umbrella – but I wouldn’t deliberately break an umbrella.

“Give it back!”

“Make me!”

The chase went around and around the playground, gathering onlookers.

One of which was the school principal, Sister Stella.

“Come here!” She shouted.

The boy with the umbrella responded to her authoritative shout with a hanging head, dragging my umbrella behind him. I followed, feeling smug. I was going to get my umbrella back and he was going to get in trouble. Justice was about to be served.

She grabbed the umbrella from him and beat him with it. I can’t recall how she beat him, possibly a general thwacking about the body.

Good, that’s what he deserved, the umbrella thief, I was thinking. I waited to have the umbrella returned to me, perhaps with some degree of sympathy for the trauma I had endured.

No.

Instead Sister Stella took the umbrella and started to beat me as well.

“That’s what you get for chasing boys,” she said.

The boys walked off, the thief no doubt getting some kind of kudos from his friends for surviving a beating and berating from the school principal.

I was left with my umbrella and my friends. I started crying because of the extreme injustice of it all and then used a particular bad swear word for the first time in my young life, so angry and upset I was. Explain to me how this works: he steals my umbrella, laughs at me for not being able to get it back off him, pretends he’s going to break my property, and I get beaten for that?

These days I guess we would call it victim blaming.

Back then Sister Stella would have seen a girl chasing a boy as “trouble”, and if I hadn’t done something wrong already, I was probably contemplating it, so from her point of view the beating was pre-emptive.

In reflection, I do have lots of happy memories of primary school. I had some good teachers (some of whom I’ll talk about in future posts, I hope). I had friends, I had a bicycle, I even (who knows how) loved learning music. But these memories, these individual moments, these left marks on me. Maybe it was an early lesson that the world isn’t fair. (I might learn that but I don’t have to like it.) Maybe it was the importance of practising to improve a skill (and avoid a beating). Not all of school’s lessons are learnt in the classroom.